This article is on one of the vexatious issues of taxation on the software payments made by residents to non-residents. The said issue was put to an end by the Honourable Supreme Court in the matter of Engineering Analysis Centre of Excellence Private Limited[1] (for brevity ‘EAC’) in favour of the tax payer. Let us proceed to understand the core issues, the history involved surrounding the issue, the arguments by and against tax payer, the analysis by Supreme Court and conclusions therein.

Issue:

The issue predominantly revolves around whether the payments made by resident towards various usages of software to non-residents requires withholding obligations under Section 195 of Income Tax Act, 1961 (for brevity ‘ITA’).

The tax payer’s principle assertion (through the payer) is that since the payments were made for usage of software, the same would not fall under the definition of ‘royalty’ as provided in Explanation 2 to Section 9(1)(vi) of ITA. Further, assuming that the amendment made to Section 9(1)(vi) by inserting Explanation 4 in 2012 with retrospective effect from 1976, to make it clear that granting of license is also included in all or any of the rights involved in a copyright, the tax payer argument was that since the said amendment was not on statute book as on the date of payments to non-resident vendors, the provision cannot be applied to the matters in hand. Apart from the above, the tax payer also argued that he would be covered under the protection of Double Taxation Avoidance Arrangement (for brevity ‘DTAA’) and thereby there is no income which accrues or arise or deemed to accrue or deemed to arise in India and accordingly the payer is not required to deduct any tax under Section 195 on the payments made. The tax payer argued that what was transferred to end-user was a non-exclusive restricted license to use the software. In other words, a copyrighted article is being sold and not the copyright. The payments which are mentioned either under Section 9(1)(vi) or Article 12 of DTAA are those which cover the payments for transfer of copyrights and not deal with copyrighted article.

The Revenue’s principle assertion is that the grant of license of a computer programme, being specifically included in Explanation 4 to Section 9(1)(vi) makes the legislative intent clear to treat such payments to fall under the ambit of ‘royalty’. Since the ITA deals with the definition of ‘royalty’, there is no requirement to look for the meaning under Copyright Act, 1957 (for brevity ‘Copyright Act’). Further, all the DTAAs define the ‘royalty’ to mean payment of consideration for use or right to use the copyright. Since the subject payments are for use or right to use the computer software, the said payments are obviously covered under the DTAA and accordingly the payer is required to withhold tax on the same. Further, the Revenue also stated that the retrospective amendment made qua Explanation 4 is only for removal of the doubts and has to be interpreted not as a new thing. The Revenue argued that derivative product of copyright is also covered under the ambit of Section 9(1)(vi) and thereby payment made for usage of software would mean to accrue or arise or deemed to accrue or deemed to arise in India for the non-resident vendors. The revenue also stated that in certain facts of the appeals, the agreement involved is the distribution agreement with the non-resident, by virtue of entering the distribution agreement the non-resident parted with the rights mentioned in Section 14(b)(ii) of Copyright Act and accordingly the payment would fall under the ambit of ‘royalty’, since the said payment was a consideration for transfer of all or any of the rights mentioned in Section 14.

With the above in place, let us proceed to examine, the history of the issue and the other aspects connected.

History:

The facts in the matter of EAC, a resident Indian company has purchased an end-user shrink wrapped computer software, directly imported from United States of America (for brevity ‘USA’). The payment was made for the shrink wrapped computer software without any deduction of tax at source. The tax authorities opined that the said payment for shrink wrapped computer software involves payment for copyright which attracted the payment of royalty under both Article 12(3) of Indo-USA DTAA and Section 9(1)(vi) of ITA. The EAC pleaded that the subject payment is only for usage of the software but does not involve any payment for the copyright and cannot be categorised as royalty, which would required withholding of tax. The Assessing Officer was not convinced with the submissions has upheld the order confirming the withholding of tax. The matter when taken to Commissioner (Appeals) was held against EAC. However, EAC succeeded before the Tribunal. The Tribunal following its earlier judgment in Samsung Electronics Co. Limited has dismissed the order of Commissioner (Appeals) and held that there was no obligation on the EAC to withhold any tax. Aggrieved by this, the Revenue has preferred an appeal to High Court of Karnataka. The High Court of Karnataka hearing the matter of EAC along with other clubbed appeals, framed nine questions of which, two of them deal with issue of copyright.

The High Court after framing of the questions, without venturing into the merits, has concluded that the payments made by end-users for purchase of software requires deduction of tax at source. The High Court has passed the above judgment vide its order dated 24.09.2009. The High Court has majorly placed reliance on the decision of Supreme Court in the matter of Transmission Corporation of AP Limited[2] for arriving the said conclusion. The High Court accepted the submissions by revenue that unless the payer makes an application under Section 195(2) and has obtained a permission for non-deduction of tax, it was not permissible for the payer to contend that the payment made to non-resident did not give rise to income taxable in India.

The above judgment of High Court of Karnataka was appealed before the Honourable Supreme Court in a batch of appeals. The Supreme Court after detailing the facts and analysing the judgment of Transmission Corporation of AP Limited (supra) stated that the High Court of Karnataka has misunderstood the ratio in the matter of Transmission Corporation of AP Limited (supra) and thereby misapplied the same in the matter of Samsung Electrical Co. Limited[3] (supra) and reiterated that every payment made to non-resident would not require deduction of tax at source and only such payments which are chargeable to tax in India would only fall under the ambit of the withholding obligation. This became a landmark judgment by Supreme Court in the matter of GE Technology Centre Private Limited[4][5]. The said judgment reversed the decision of High Court of Karnataka in the matter of Samsung Electrical Co. Limited and asked the High Court to consider the matter at fresh.

When the matter came for the second time before the High Court of Karnataka, vide its judgment dated 15.10.11 in the matter of Samsung Electrical Co. Limited[6] held that, what was sold by way of a computer software included a right or interest in copyright, which thus gave rise to payment of royalty and would be an income deemed to accrue in India in terms of Section 9(1)(vi) and accordingly obligating the payer to deduct tax. This was challenged before Supreme Court, where the Court has taken EAC as the lead matter for analysing the facts involved and to arrive at a conclusion.

Arguments:

As discussed earlier, the current matter involves a large number of petitions which involve determination of taxation on various usages of software. Based on the facts involved, the apex court has basketed them into four broad categories, which are as under:

Arguments by Tax Payers:

The facts are that the resident Indian Companies are non-exclusive distributors of computer software. They purchase off-the shelf copies of shrink wrapped software from foreign companies for onward sale to Indian end-users under a remarketer agreement.

On Taxation:

The tax payer has asserted that the Indian distributor is not a party to the End User License Agreement (for brevity ‘EULA’) between the end-user and the foreign supplier. The tax payer’s argument was that they simply do not own any right, title or interest in copyright or other intellectual property owned by the foreign supplier and they just market the foreign supplier’s software. The end-user pays to the Indian distributors and after retaining certain part as profit, the Indian distributors pays to the foreign supplier. Hence, the amounts paid by the Indian distributor does not partake the character of royalty since the payment is not made for any rights involved. The tax payer also stated that the computer software imported for onward sale constitutes as ‘goods’ in light of the Supreme Court judgment in Tata Consultancy Services[8]. The tax payer also making reference to DTAAs in place, stated that the DTAAs do not cover the derivatives products of royalties and cover only the core right and assuming that Section 9(1)(vi) covers the current payment as royalty, in terms of Section 90(2), the beneficial provisions of DTAA has to be invoked and accordingly there is no income which would accrue to the foreign supplier in India and accordingly the Indian distributor is not obligated to withhold the tax.

The tax payer has also submitted that the Explanation 4 inserted to Section 9(1)(vi) vide Finance Act, 2012 giving retrospective effect from 1976 also can cover only ‘any right, property or information used or services utilised’ but cannot be read to expand the definition of ‘royalty’ as contained in Explanation 2 to Section 9(1)(vi). The tax payer has also challenged that the Explanation 4 cannot be pressed into service since it would compel them to do an impossible task, since at the time of making the payment, the said explanation was not in vogue. Hence, on a retrospect, the revenue cannot ask the payer to withhold taxes.

On Copyright Act:

The tax payer further making reference to the Copyright Act, 1957 (for brevity ‘Copyright Act’) asserted that there is a difference between copyright in an original work and copyrighted article. Under the remarketer agreement, no copyright would be given by the foreign supplier to the Indian distributor or the end-user. The end-user is only entitled only a limited license to use the product by itself, with no right to sub-license, lease, make copies. Hence, the said limited right parted by foreign supplier would not fall under the ambit of ‘royalty’ as envisaged in DTAAs.

The tax payer has stated that the amendment to Section 14(b)(ii) of Copyright Act with effect from 2000 by removing the words ‘regardless of whether such copy has been sold or given on hire on earlier occasions’ is a statutory application of the doctrine of first sale/principle of exhaustion. The amendment made it clear that since no distribution right by the original owner extended beyond the first sale of the copyrighted goods, it can be said that only the goods has been passed to the imported and not the copyrights in the goods.

Arguments by Revenue:

On Taxation:

The Revenue’s principal argument was that the introduction of Explanation 4 to Section 9(1)(vi) is only a clarificatory in nature and accordingly the payer was obliged to deduct taxes even such explanation was not on statue book as on the date of payment. The Revenue stressed that importance has to be given to phrase ‘in respect of’ appearing in Explanation 2(v) of Section 9(1)(vi) to bring home the point that derivate products of copyright are also covered under the ambit of ‘royalty’. The Revenue placed reliance on decision on PILCOM[9], wherein it was held that irrespective of the fact that the payment was chargeable to tax in India, the payer has to withhold tax. The PILCOM judgment was in the context of Section 194E.

On Copyright Act:

The Revenue stated that since in some of the cases, adaptation of software could be made, albeit for installation and use on a particular computer, the same would be possible only if the original owner has parted with his copyrights and asked to consider that such payments would be falling under the ambit of ‘royalty’. The Revenue also stated that in terms of Section 52(1)(ad) of Copyright Act, that only making copies or adaptation of a computer programme from a legally obtained copy for non-commercial, personal use would not amount to infringement, and in cases where the same are copied for commercial purpose would constitute infringement and in certain cases, the same were being copied for commercial purposes would result in infringement, thereby meaning that the original owner has parted the rights therein. In light of the above, the Revenue stated that the payments were for royalties and accordingly the payer would have to withheld taxes at source and failing to do so, the tax payers has not met the obligations.

Analysis by Supreme Court:

The Supreme Court after setting out the provisions of ITA and Copyright Act has brushed away the argument of Revenue which canvassed the view that the payer has to withhold tax at source even such income is not chargeable to tax in India. The Court stated that Section 195 is clear to state that the obligation of withholding would trigger only if such income was chargeable to tax in India, which is again determined by applying the provisions of Section 5 read with Section 9. The Court reiterated that the above position is made abundantly clear in the matter of GE Technology Centre Private Limited (supra). The Court also brushed the reliance of Revenue in the matter of PILCOM (supra) stating that, the said judgment was in the context of Section 194E and not under Section 195. The Court stated that the provisions of Section 194E does not have any reference to chargeability of income under the provisions of ITA, which do find a place in Section 195. Hence, the decision in PILCOM which was dealing on obligation of withholding of tax for payments made under Section 194E, which do not have reference to any chargeable to tax in India cannot be applied to situation under Section 195.

The Court stated that though the phrase ‘copyright’ has not been defined in the Copyright Act separately, the provisions of Section 14 of the said act makes it clear that ‘copyright’ to mean the ‘exclusive right’ subject to provisions of the act, to do or authorise the doing of certain acts ‘in respect of a work’. Thus, when an author in relation to ‘literary work’ which includes a ‘computer programme’, creates such work, such author has an exclusive right, subject to the provision of the Act, to do or authorise the doing of several acts in respect of such work. When the owner of copyright in a literary work assigns wholly or in part, all of any rights contained in Section 14(a) and (b), in the said work for a consideration, the assignee of such right becomes entitled to all such rights comprised in the copyright that is assigned, and shall be treated as owner of copyright of what is assigned to him. Further, the owner of copyright in any literary work may grant any interest in any right mentioned in Section 14(a) by license in writing by him to the licensee, under which, for parting with such interest, royalty becomes payable. When such license is granted, copyright is infringed when any use, relatable to the said right/interest that is licensed, is contrary to the conditions of the license so granted. Hence, if the right parted by the original owner/author is to allow another person to reproduce and commercially exploit the intellectual property involved, then the person would not be said to be infringing the copyright since he has not violated any conditions of the license. Accordingly, the Court brushed away the plea of Revenue, wherein it was asserted that making copies of copyright and using them would mean infringement of copyright.

Reproduction vs Usage:

The Court then referring to the conditions in various contracts has stated that what is granted to the distributors is only a non-exclusive, non-transferable license to resell computer software and it is expressly stated that no copyright in the computer programme is transferred either to the distributor or to the end-user. The Court stated that the distributor retains only part of the consideration as profit and the retention is also for the reason that the distributor is a reseller but not because he has obtained a right to use the product. Further, the end-user who is directly sold the computer programme, can use only it by installing it in the computer hardware owned by the end-user and cannot in any manner reproduce the same for sale or transfer, contrary to the term of EULA. The Court stated that none of the facts involved in the current appeals involves grant of license in terms of Section 30 of Copyright Act, which transfers an interest in all or any of the rights contained in Section 14(a) and 14(b). The Court stated that only such grant of licenses which fall under the category of Section 30 can be said to be grant of copyright in order to characterise the income arising thereof as a royalty. Since all the EULAs impose restrictions or conditions for use of computer software, it cannot be said what was granted was a license in terms of Section 30. The Court took an example to elucidate the said point. If an English publisher sells 2000 copies of a particular book to an Indian distributor, who then resells the same at a profit, no copyright in the aforesaid book is transferred to the Indian distributor, either by way of license or otherwise, in as much as the Indian distributor only makes a profit on the sale of each book. Importantly, there is no right in the Indian distributor to reproduce the aforesaid book and then sell the copies of the same. On the other hand, if an English publisher were to sell the same book to an Indian publisher, this time with the right to reproduce and make copies of the aforesaid book with permission of the author, it can be said that copyright in the book has been transferred by way of license or otherwise, and what the Indian publisher will pay for, is for the right to reproduce the book, which can then be characterised as royalty for the exclusive right to reproduce the book in the territory mentioned by the license.

The Court then proceeded to make a reference to the judgment of State Bank of India[10] which was under the Customs Act, 1962 (for brevity ‘Custom Laws’). The issue involved therein is State Bank of India has imported a consignment of computer software and manual from Kindle Software Limited, Ireland and cleared the goods for home consumption on payment of customs duty. State Bank of India has filed a refund application stating that interpretative note relating to Rule 9(1)(c) of Customs Valuation (Determination of Price of Imported Goods) Rules, 1998 suggests that royalties and licenses paid for right to reproduce the imported goods should not be added to the price actually paid or payable. State Bank of India has taken a plea that since the software imported involves right to reproduce, the royalties paid should not be added to the assessable value of the goods. Since the same were already included, State Bank of India has applied for refund. The Court in the said matter made an important observation vide Para 21. It stated that reproduction and use are two different things. Since in the facts of State Bank of India, what was permitted by Kindle Software Limited is use but not the right to reproduce. The Court stated that what was paid by State Bank of India was for the license and not the right to reproduce and accordingly State Bank of India would not be eligible for refund. Taking clue from the above judgment, the Supreme Court in the matter of EAC stated that the right to reproduce would entail parting of copyright and whereas right to use does not entail any copyright.

The Court also referring to the real nature of transactions involved stated that what is licensed by foreign, non-resident supplier to the distributor and resold to the resident end-user, or directly supplied to end-user, is in fact the sale of a physical object which contains an embedded computer programme and therefore, essentially a sale of goods as held by the Supreme Court in the matter of Tata Consultancy Servies (supra).

The Supreme Court then proceeded to analyse the definition of ‘royalty’ in the context of DTAA and ITA. The Court analysed that the definition under Article 12(3) of Indo-Singapore DTAA which deals with ‘royalty’ is exhaustive and differs with the definition under the local law at least in three aspects. The main aspect under the provision of ITA is the presence of Explanation 2(v) to Section 9(1)(vi). Vide such part of the explanation, ‘the transfer of all or any rights (including the granting of license) in respect of copyright, literary, artistic or scientific work including..’ is covered under the definition of ‘royalty’. Harping on this, the Revenue contested that the consideration received by foreign supplier for granting of license comes under the ambit of ‘royalty’ because it specifically gets mentioned in Explanation 2(v).

However, the Supreme Court rejected the above contention by stating that a payment to fall under the ambit of Explanation 2(v) should in the first place involve transfer of all or any rights. The rights that are being discussed are the rights that were mentioned in Section 14(a), Section 14(b) and Section 30 of Copyright Act. Hence, unless the rights which are mentioned in Section 14(a) and Section 14(b) are transferred either in full or any, there is nothing which falls under the ambit of Explanation 2(v). The phrase ‘including the granting of license’ has also to be read to mean that the grant of license includes the parting of rights as mentioned in Section 14(a) and Section 14(b). Since in all the matters, the facts involved the granting of license which is not in the nature of Section 14(a) and Section 14(b), such consideration arising for grant shall not fall under the ambit of Explanation 2(v) to Section 9(1)(vi).

Conclusions by Supreme Court:

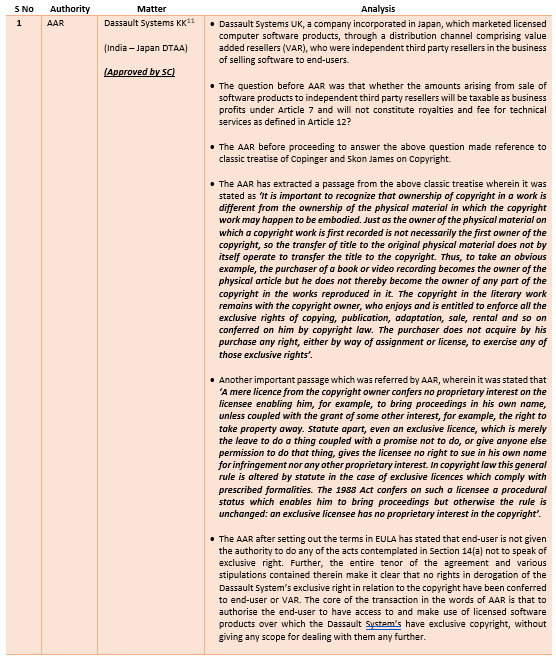

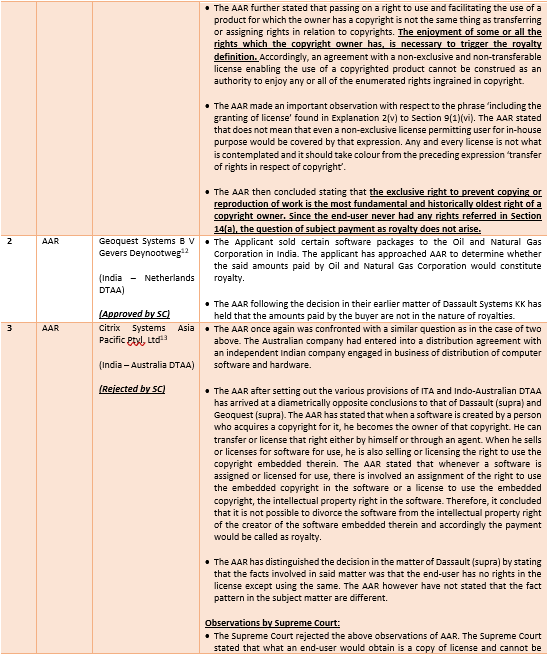

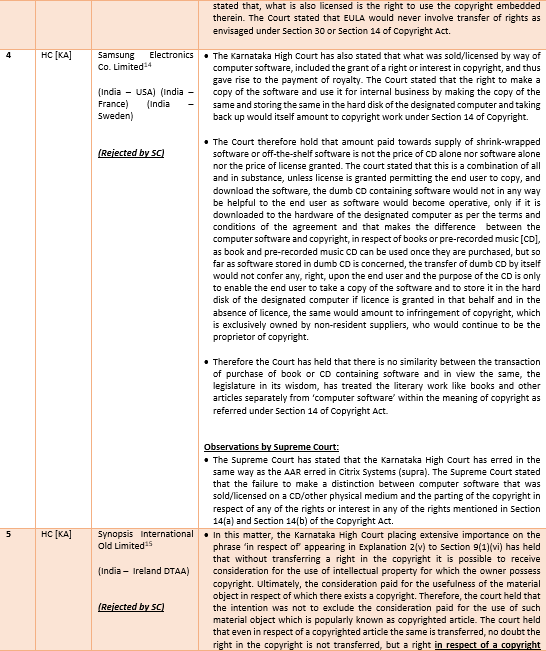

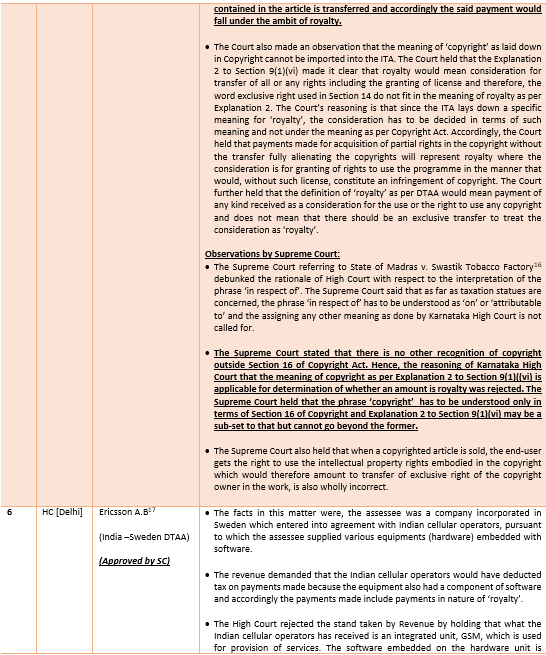

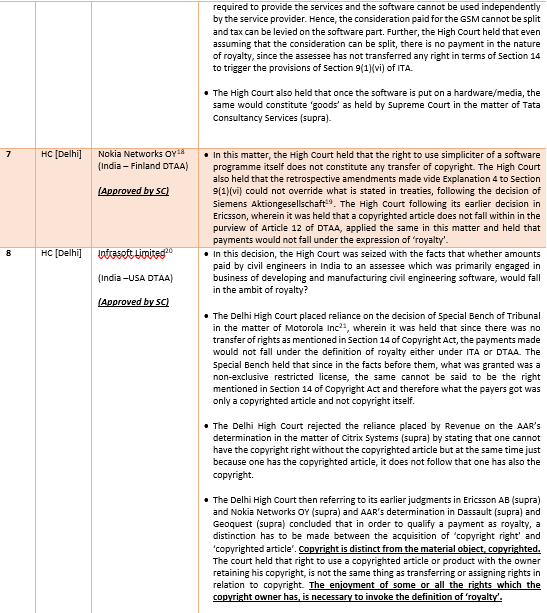

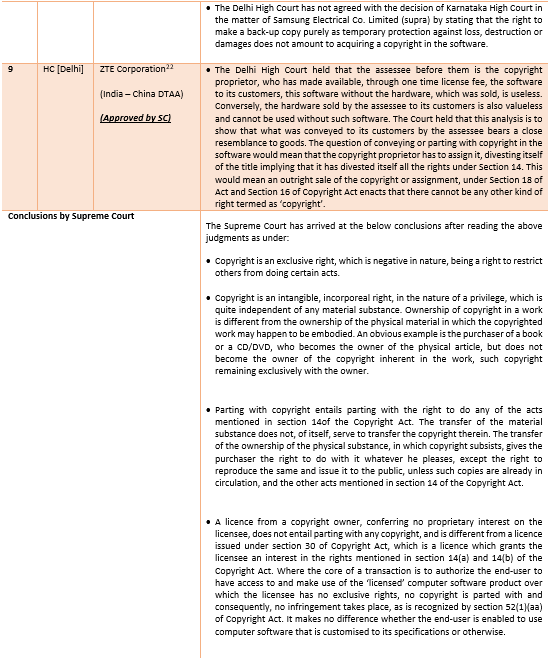

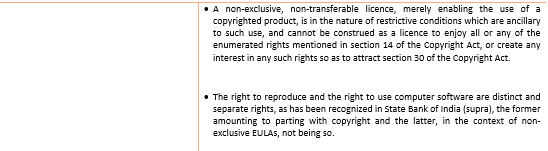

The Supreme Court then proceeded to analyse the various judgments issued by Authority for Advance Ruling (for brevity ‘AAR’), Tribunals and High Courts. The discussion can be summarised as under:

Doctrine of First Sale/Principle of Exhaustion:

The Supreme Court then proceeded to analyse the concept of doctrine of first sale/principle of exhaustion. The Revenue’s contention was that on the facts of the cases involved in appeal, the doctrine of first sale/principle of exhaustion would have no application inasmuch as the doctrine is not statutorily recognised in Section 14(1)(b)(ii) of Copyright Act. This being so, the revenue contended that since the distributors of copyrighted software license or sell such computer software to end-users, there would be parting of a right or interest in copyright inasmuch as such license or sale would then hit by Section 14(b)(ii).

The Supreme Court rejected the above contention by referring to Copinger and Skone James on Copyright, wherein it was stated that an important aspect of the distribution right is that it is exhausted in relation to a particular article by the first sale of that article in community by the right holder or with his consent. The Court then proceeded to refer to the judgment of Delhi High Court in the matter of Warner Bros. Entertainment v. Santosh V G[23] , wherein the concept of doctrine of first sale/principle of exhaustion was discussed. The Delhi Court vide Para 58 stated that exhaustion right is linked to the distribution right and the right to distribute objects (making them available to the public) means that such objects (or the medium on which work is fixed) are released by or with the consent of the owner as a result of the transfer of ownership. The court stated that in this way, the owner is in control of the distribution of copies since he decides the time and form in which copies are released to public. Content-wise the distribution right are to be understood as an opportunity to provide the public with copies of work and put them into a circulation, as well as to control the way the copies are used. The exhaustion of rights principle thus limits the distribution right, by excluding control over the use of copies after they have been put into circulation for the first time.

The Supreme Court after referring to the judgment of European Court of Justice in the matter of UsedSoft GmbH v. Oracle International Corp[24] and judgment of United States Court of Appeal for the Ninth Circuit in matter of Verner v. Autodesk Inc[25] has concluded that the doctrine of first sale/principle of exhaustion is dependent, in the first place, upon legislation which either recognises or refuses to recognise the doctrine (thereby continuing to vest distribution right in the copyright owner, even beyond the first sale of copyrighted article). The Supreme Court stated that prior to the amendment in 2012 to Section 14(d)(ii), which deals with cinematograph film, the legislative intent is clear to refuse to recognise the doctrine of first sale. In other words, prior to amendment, the copyright owner would continue to control the distribution rights even beyond the first sale of copyrighted work. However, post 2012, the amendment dropping the phrase ‘regardless of whether such copy had been sold or given on hire on earlier occasion’, the legislative intent is clear to recognise the doctrine of first sale. In other words, post amendment, the copyright owner does not continue to have the distribution right post the first sale.

In similar way, the Supreme Court stated that Section 14(b)(ii) has also been amended in 2000, to delete the phrase ‘regardless of whether such copy had been sold or given on hire on earlier occasion’, thereby making it clear that the tilt has been in favour of the purchaser. The Court further stated that language of Section 14(b)(ii) of Copyright Act makes it clear that is the exclusive right of the owner to sell or to give on commercial rental or offer for sale for commercial rental ‘any copy of the computer programme’. The Court stated that a distributor who purchases computer software in material form and resells it to an end-user cannot be said to be within the scope of above said provision for the reason that ‘any copy of computer programme’ would mean that the same would apply to making the copies of the computer programme and then selling them, i.e., reproduction of the same for sale or commercial rental.

The Supreme Court stated that the object of Section 14(b)(ii) is to prohibit reproduction of the said computer programme and consequent transfer of the reproduced computer programme to subsequent acquirers/end-users. Hence, the distributor who is engaged in resale of the computer programme does not get in the way of Section 14(b)(ii). The Court concluded that once it is understood that the object of Section 14(b)(ii) is not to prohibit the sale of computer software that is ‘licensed’ to be sold by a distributor, but that it is to prevent copies of computer software once sold being reproduced and then transferred by way of sale or otherwise, it becomes clear that any sale by the author of a computer software to a distributor for onward sale to an end-user, cannot possibly be hit by the said provision. Accordingly, the Court concluded that the contention of Revenue that the distribution of copyrighted computer software would constitute grant of an interest in copyright under Section 14(b)(ii) cannot be accepted.

Accordingly, the Supreme Court concluded that amounts paid by resident Indian end-users/distributors to non-resident computer software manufacturers/suppliers, as consideration for resale or use of the computer software through EULAs/distribution agreement, is not the payment of royalty for the use of copyright in the computer software and the same does not give rise to any income taxable in India. The Court held that the above conclusions would apply to all the four categories.

[1] [2021] 432 ITR 471 (SC)

[2] [1999] 007 SCC 266

[3] This was a batch of appeals involving EAC matter also. The judgment was delivered in the name of lead party, which is Samsung Electrical Co. Limited.

[4] [2010] 327 ITR 456 (SC)

[5] This was a batch of appeals involving Samsung Electrical Co. Limited matter also. The judgment was delivered in the name of lead party, which is GE Technology Centre Private Limited.

[6] [2012] 345 ITR 494

[7] Non-Resident

[8] [2005] 1 SCC 308

[9] 2020 SCC Online SC 426

[10] [2001] 1 SCC 727

[11] [2010] 322 ITR 125 (AAR)

[12] [2010] 327 ITR 1 (AAR)

[13] [2012] 343 ITR 1 (AAR)

[14] [2012] 345 ITR 494

[15] 2013 (2) TMI 448

[16] (1966) 3 SCR 79

[17] [2012] 343 ITR 470

[18] [2013] 358 ITR 259

[19] 310 ITR 320 (Bom)

[20] [2014] 264 CTR 329

[21] [2005] 147 Taxman 39 (Delhi)

[22] [2017] 392 ITR 80

[23] [2009] SCC OnLine Del 835

[24] Case C – 128/211

[25] 621 F.3D 1102 (9th Cir.2010)