One of the main reasons that goods and services tax (for brevity ‘GST’) laws were introduced is to bring numerous indirect legislations under one single law to the extent possible. By doing this, the service tax law, excise law and value added tax law have repealed and subsumed into GST laws. Everyone was happy, because there is no requirement to understand, what is manufacture, what is goods, what is service, what is negative list, what is positive list and so on. Simply, the GST law promised, if there is a supply, there is a tax. However, that was so in the dream land and not in reality. We continue to face issues in different shapes and that was the only change, one can perceive.

In this article, we tried to write on the issues surrounding the job work. Before deliberating on the issues, we will take a look on the concept of job work under the GST laws. The expression ‘job work’ is laid down under Section 2(68) of CT Act[1] to mean any treatment or process undertaken by a person on goods belonging to another registered person and the expression ‘job worker’ shall be construed accordingly. Section 143 details the procedures pertaining to the job work, which we will deal at appropriate place. With the above in mind, let us now proceed to examine certain issues pertaining to job work.

Issue #1 – Can the activity of job work result in manufacture?

The definition of ‘job work’ as laid down under Section 2(68) states that any treatment or process undertaken by a person on goods belonging to another registered person. The said definition nowhere stated that the said treatment or process should not result in manufacture. Hence, if the treatment or process adopted by job worker on the inputs (goods) result into a different product from the input, the said process should still qualify as job work. The expression ‘manufacture’ is defined in Section 2(72) states to mean processing of raw materials or inputs in a manner that results in emergence of a new product having a distinct name, character and use and the term ‘manufacturer’ shall be construed accordingly.

Though the term ‘manufacture’ is defined to specifically mean a process which results in emergence of a new product and absence of similar language in the definition of ‘job work’ should not indicate that job work cannot include manufacture. In other words, manufacture is sub-set of job work. Hence, any activity or treatment, whether it results in a new product or not, shall fall under the ambit of job work.

If that was this easy, why did we frame it is an issue, would be the question. The journey to reach the above conclusion was a tiresome one. The issue came up before the Maharashtra AAR[2] in the matter of JSW Energy Limited[3]. In the facts of the matter, JSW Energy Limited (for brevity JEL) has entered an agreement with JSW Steel Limited (for brevity JSL) for conversion of coal into electricity, which can be used by later for their manufacturing of steel. By virtue of an agreement, JSL procures and supplies coal on free of cost basis to JEL, for the later to convert the said coal by using certain other items into electricity and supply back to JSL. For the said process, JEL will raise an invoice with tax. The question that came up before the Maharashtra AAR is, whether any tax is applicable on supply of coal or any other inputs on a job work basis by JSL to JEL, whether any tax is applicable on supply of power by JEL to JSL and tax implications on job work charges payable to JEL by JSL. The Maharashtra AAR without answering all the above questions has held that since the coal is converted to electricity and the said process emerging into a new product, would not fall under the definition of ‘job work’. The AAR has held that the ‘treatment or process’ used in the definition of ‘job work’ does not include the activity of manufacture and once a treatment or process results into a new product distinct from the inputs, the same would be manufacture and cannot be held as job work. The AAR stated that since the instant case, the coal is converted into electricity, which is altogether a distinct product, the said activity cannot be called as job work. The AAR continued to state that since the expression ‘manufacture’ is also laid down in CT Act, the ambit of job work cannot be extended to include the former. Finally, the AAR held that said activity carried on by JEL cannot be said to be job work and the supply of electricity is stated to be supply of goods.

JEL has taken up the matter in appeal[4] before AAAR[5]. The AAAR after going through the submissions of both the parties and the order of AAR, stated that the activity or transaction even it amounts to manufacture would fall under the ambit of job work subject to satisfaction of conditions stated under GST laws. To this extent, the AAAR overruled the ruling of AAR. However, AAAR has not stopped there, it continued to hold that, in the instant case, since the inputs supplied to JEL cannot be brought back by JSL in the same form and so, it would be in contravention to the provisions of Section 143 (which mandates the bringing back of inputs after the job work), Also, the AAAR has stated that JEL adds so much of other materials and hence, the said activity cannot be called as job work. Finally, the AAAR held that since the conversion of coal into electricity is a process, where the coal cannot be brought back to principal, that is JSL, the said activity cannot be said to be job work, specifically for the reason that the provisions of Section 143 are not complied. Though the AAAR has felt that treatment or process which results into manufacture can be covered under the ambit of ‘job work’, since the conditions stated in Section 143 are not satisfied, they have held that such activity cannot be called as job work.

JEL has challenged the above order for a judicial review before the Bombay High Court[6]. The Bombay High Court stated that though there are no appeal provisions to challenge an order of AAAR in the provisions of the GST laws, the order of AAAR can be scrutinised qua judicial review[7]. Accordingly, the High Court after going through all the facts and orders passed by AAR and AAAR, held that AAAR has not complies with the principles of natural justice by not affording enough time to JEL for production of documents and other information and remanded the matter to AAAR for consideration of the documents and other information and accordingly pass an appropriate order.

In remand order passed by AAAR[8], the AAAR reversed their earlier view that coal not being an input for manufacture of steel but an input for manufacture of electricity, the said coal cannot be called as input qua JSL. Since the law states that the principal (JSL) has to send inputs to the job worker (JEL) and coal not being an input for JSL, the procedure stated under Section 143 does not apply. In the remand order passed, the AAAR stated that in light of the Circular issued by Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs (for brevity ‘CBIC’) in 79/53/2018- GST dated 31.12.2018 [wherein it is clarified that coal being an input used in the production of aluminium, albeit indirectly through the captive generation of electricity, which is directly connected with the business of registered, the input tax of coal cannot be denied] and placing reliance on the judgment of Supreme Court in the matter of Maruti Suzuki Limited[9] [wherein it was held that power generation is a captive arrangement and requirements carrying out the manufacturing activity, power generation forms part of the manufacturing activity and ‘inputs’ used in the power generation would be treated as inputs used in the manufacture of final products] reversed their earlier view and allowed that the coal is an input qua JSL.

The AAAR also reversed their earlier view that since coal is converted into electricity and not received by JSL in the same form as sent to JEL, the same does not amount to job work, since the condition that the inputs should brought back by principal was not satisfied. The AAAR by placing reliance on judgment of Bombay High Court in the matter of Indorama Textiles Limited, subsequently upheld by Supreme Court[10], wherein it was established as electricity can be generated on job work basis, hence, it is not necessary that inputs going to job worker should be received in same manner, reversed the earlier order and accordingly held that said activity undertaken by JEL would qualify as job work though it amounts to manufacture.

From the above, we can conclude that the ‘job work’ and ‘manufacture’ are not mutually exclusive. A manufacture can be forming part as sub-set to ‘job work’ and such process still will be called as ‘job work’, despite of the fact the inputs lose their shape and form. Further, Explanation to Section 143 in clear terms state that for the purposes of job work, input includes intermediate goods arising from any treatment or process carried out on the inputs by the principal or job worker. In light of the above, an irresistible conclusion is that the activity or treatment can still be a job work for the purposes of GST law, though such activity or treatment results in emergence of new product.

Issue #2 Should the activity be a manufacture, a must for job work?

In some instances, another question that arises is, whether the activity or treatment should definitely amount to manufacture to be qualified as job work. This arises mainly for the purposes of availment of concessional rate that is normally available for job work. Let us take an example to better understand this particular issue.

An exporter is engaged in export of processed prawns. For exporting the said goods, the exporter appoints a job worker for undertaking the entire process to arrive at the export goods. The process adopted by job worker would normally involve, cutting off heads and tails, peeling and deveining, cleaning and freezing. After the said process, the processed prawns are sent to exporter, from where, the same would be exported. The job worker would raise an invoice for his service and charges the concessional rate of 5% as per Entry 26(i)(f) of Notification No 11/2017 – CT (R) dated 28.06.2017.

The question that arises is, whether for adopting the concessional rate of 5%, the services provided by job worker should mandatorily be ‘manufacturing’? This is more because for the reason that Entry 26 of NN 11/2017 – CT (R) states ‘Manufacturing services on physical inputs (goods) owned by others’. The tax authorities may state that since the process adopted by the job worker does not amount to manufacture, they are not eligible for the concessional rate available under Entry 26, in light of the interpretation that the said entry covers manufacturing services alone.

On a perusal of stand that may be taken by tax authorities, it can be understood that the principal contention of the authorities would be that, the process adopted by job worker does not amount to manufacture and accordingly the rate of tax as stated in Entry 26(i)(f) would not be applicable and the services would fall under the residual category of attracting tax at 18%.

Entry 26 deals with ‘manufacturing services on physical inputs (goods) owned by others’. The said entry has 9 main entries and various sub-entries. The main entry (i) has 11 sub-entries. Further, the main entry (i) deals with ‘services by way of job work in relation to’. In other words, in order to fall under the Entry 26(i), the services provided should be by way of job work.

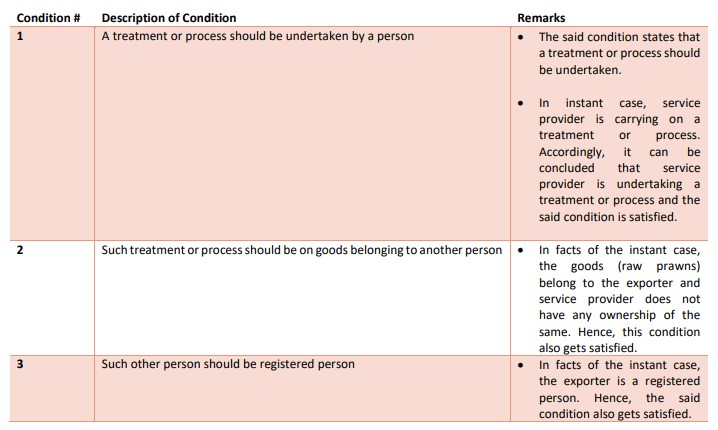

From the definition of ‘job work’ stated earlier, it is evident that, if the following conditions are satisfied the said services would fall under the ambit of the definition of ‘job work’ as laid down in Section 2(68) and service provider would be construed as job worker. Let us examine, if the conditions are satisfied by the service provider or not:

Hence, all the conditions as specified in the definition of ‘job work’ are satisfied and accordingly it can be argued that service provider can be construed as job worker and accordingly, service provider can access the sub-entries of Entry 26(i) of NN 11/17 – CT (R). Now, let us examine, whether the services provided by service provider would fall under sub-entry (f) of Entry 26(i).

The said sub-entry deals with ‘all food and food products falling under Chapter 1 to 22 in the First Schedule to the Customs Tariff Act, 1975’. Hence, on a combined reading of the main and sub-entry, it would be as under:

Services provided by way of job work in relation to all food and food products falling under Chapter 1 to 22 in the First Schedule to the Customs Tariff Act, 1975

From the above, it is evident that if service provider is providing services by way of job work in relation to food products falling under Chapter 1 to 22 in First Schedule to the Customs Tariff Act, 1975, then it can be concluded that the services would fall under Entry 26(i)(f). Since prawns fall under Chapter 3 of First Schedule, they would fit under the sub-entry (f). Hence, all the conditions mentioned in Entry 26(i)(f) of NN 11/17 – CT (R) gets satisfied.

Since all the conditions mentioned in Entry 26(i)(f) are satisfied by service provider, the rate of tax of 5% is applicable to the services provided by job worker to the exporter. Now, let us examine the force in the allegations of the probable stand that may be taken by tax authorities, that the services provided are not manufacture, accordingly the rate of tax as mentioned Entry 26(i)(f) is not to be applied.

In this connection, it is important to note that the allegation of tax authorities that the activity or process should satisfy the definition of ‘manufacture’ appears to be only based on the heading of Entry 26 ‘manufacturing services on physical inputs (goods) owned by others’. In other words, since the said entry deals with manufacturing services, the tax authorities are of the opinion that only such process or treatment undertaken by job worker which result in manufacture are only covered under the said entry. However, on a detailed perusal of the various sub-entries post a different view. The list of sub-entries is as under:

- Printing of newspapers

- Textiles and Textile products falling under Chapter 50 to 63 in First Schedule to CTA[11]

- All products, other than diamonds falling under Chapter 71 in First Schedule to CTA

- Printing of Books (including Braille books), journals and periodicals

- Printing of all goods falling under Chapter 48 or 49, which attract tax at 2.5% or nil

- Processing of hides, skins and leather falling under Chapter 41 in First Schedule to CTA

- Manufacture of leather goods or foot wear falling under Chapter 42 or 64 in First Schedule to CTA

- All food and food products falling under Chapter 1 to 22 in First Schedule to CTA

- All products falling under Chapter 23 in First Schedule to CTA except dog and cat food put up for retail

- Manufacture of clay bricks falling under Tariff 69010010 in First Schedule to CTA

- Manufacture of handicraft goods

From the above, it is evident that the sub-entries ea, f and i, specifically have a mention of ‘manufacture’ and other entries do not have. Hence, it can be understood, wherever the legislature intends to give a concessional rate for the process or treatment which should amount to manufacture, the same was explicitly mentioned. In other words, the sub-entry (f) does not have mention of ‘manufacture’ to it. Hence, even though the treatment or process does not amount to manufacture, still the said services would qualify for concessional rate of 5%. Hence, the allegation of the tax authorities that the said process should be manufacture for being eligible for concessional rate may not be in accordance with the law. The said view is also supported by the explanatory notes to scheme of classification of services[12], at Page 92. From the above, it is evident that the process or treatment need not be manufacturing activity and also the entry covers the portions of manufacturing process. Since, the treatment of conversion of raw prawns and shrimps is part of the manufacturing process, the services supplied by ABC would be eligible under Entry 26(i)(f) and be taxable at 5%.

Hence, from the above, it can be understood that the certain activities or process need not be amounting to ‘manufacture’ to be adopting the concessional rate.

[1] Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017

[2] Authority for Advance Ruling

[3] 2018 (5) TMI 763 – Maha AAR

[4] 2018 (7) TMI 511 – AAAR Maha

[5] Appellate Authority for Advance Ruling

[6] 2019 (6) TMI 717 – Bombay High Court

[7] Under judicial review, the Court does not goes into merits of case, but questions whether the process involved to arrive the conclusion by the lower authority is in accordance with the law.

[8] 2020 (6) TMI 704 – AAAR Maha

[9] 2009 (8) TMI – Supreme Court

[10] 2010 (260) ELT 83 (SC)

[11] Customs Tariff Act, 1975