History:

Prior to introduction of Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act in 1988, the benami transactions were recognised as a specie of legal transactions pertaining to immovable properties. The nature of a benami transaction has been described by the Judicial Committee of Privy Council in Gurnarayan v Shoelal Singh[1], thus –

The system of acquiring and holding property and even of carrying on business in names other than those of the real owners, usually called the benami system, is and has been a common practice in the country ….. The rule applicable to benami transactions was stated with considerable distinctness in a judgment of this Board delivered by Sir George Farewell. Referring to a benami dealing, their Lordships say: It is quite objectionable and has a curious resemblance to the doctrine of our English law that the trust of the legal estate results to the man who pays the purchase money, and this again follows the analogy of the common law that where a feoffment is made without consideration the use results to feoffer.

So long, therefore, as a benami transaction does not contravene the provisions of the law, the courts are bound to give it effect. As already observed, the benamidar has no beneficial interest in the property or business that stands in his name; he represents, in fact, the real owner, and so far as their relative legal position is concerned, he is a mere trustee for him…..”

(57th Report of Law Commission)

As between the benamidar and the real owner, the law fully recognised the ownership of real owner, and disregards the benamidar subject to certain statutory exceptions. However, after understanding the evils of the benami transaction, an ordinance was brought in to prohibit the real owner to recover the property from the benamidar, thus, legislatively putting an end to the encouragement benami transactions.

Journey till now:

An ordinance was promulgated which was titled as Benami Transactions (Prohibitions of the Right to Recovery Property) Ordinance, 1988. The ordinance contained 4 sections and the main object of the ordinance is to prohibit the right to recover property held benami. Section 4 of the ordinance provides for repeal of various sections in different legislations which subtly provide for the right to the real owner to recover the property from the benamidar.

Post promulgation of above Ordinance, the Law Commission was asked to take up the provisions of Ordinance for detailed examination and give its report. The Law Commission has given its suggestions and incorporating the same, the Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988 (‘original Act’) was passed repealing the Ordinance. The Act contained 9 sections and the preamble of the act states as ‘to prohibit the benami transactions and right to recover property held benami and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto’.

Section 3 prohibits benami transactions. Section 4 prohibits right to recover property held as benami and Section 5 provides for acquisition of benami properties. Section 6 specifies that nothing stated in this act shall affect the provisions of Transfer of Property Act, 1882 or any law relating to transfers for illegal purposes. Section 7 repeals Section 81, 82 and 94 of the Indian Trusts Act, Section 66 of Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 and Section 281A of IT Act, 1961. Section 8 confers the rule making power on Central Government and Section 9 repeals Ordinance with savings clause.

Because the 1988 act does not have the provisions relating to confiscation, appeal mechanism and other procedures, the act could not be implemented effectively. The Standing Committee on Finance in 2011-12 vide Report 58 recommended to repeal the 1988 act and introduce 2011 Bill to cure the infirmities the 1988 act possesses. However, the bill could not be passed since the Lok Sabha has dissolved and accordingly the bill got lapsed.

In 2015-16, the Standing Committee on Finance vide Report 28 stated that an amendment Act has to be passed to cure the infirmities the 1988 has. The reasoning laid down by Standing Committee to pass an Amendment Act instead of New Act is as under:

In this context it is submitted that a new bill incorporating the above features was prepared and forwarded to the Ministry of Law. In the Repeals and Saving clause a specific sub-clause had been included, so as to ensure that any benami transaction which had been undertaken by any person between the year 1988 and date of proposed bill coming into force, was also covered under new legislation. This implied that Benami Transactions, on which no action was taken under the 1988 Act, would be recognized as benami transaction under new act, and consequential action would follow. The Ministry of Law was of the opinion that aforesaid provision was unconstitutional in view of Article 20 of Constitution, and therefore could not be included in repeals and savings. Therefore, no action would be possible on any such transactions which occurred between 1988 and the date of repeal of 1988 Act. As a consequence, the Benami transactions during the period of twenty six years, would be in fact granted immunity since no action could be initiated in absence of specific provision in Repeals and Savings clause. It was therefore suggested by Ministry of Law, that it would be advisable to comprehensively amend the existing Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988, so that the offences committed during the last 26 years are also covered. This would enable action against Benami transactions undertaken after the commencement of 1988 Act. Therefore, the present Bill is an Amendment Bill and not a Bill proposing a new Act.

Accordingly, Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Amendment Act, 2016 (‘amendment Act’) was passed, which came into effect from 01st November 2016. The amendment Act contains detailed provisions, which were absent in the original Act. The amendment Act has also laid down the guidelines required for attachment and other related matters.

Challenge before Supreme Court:

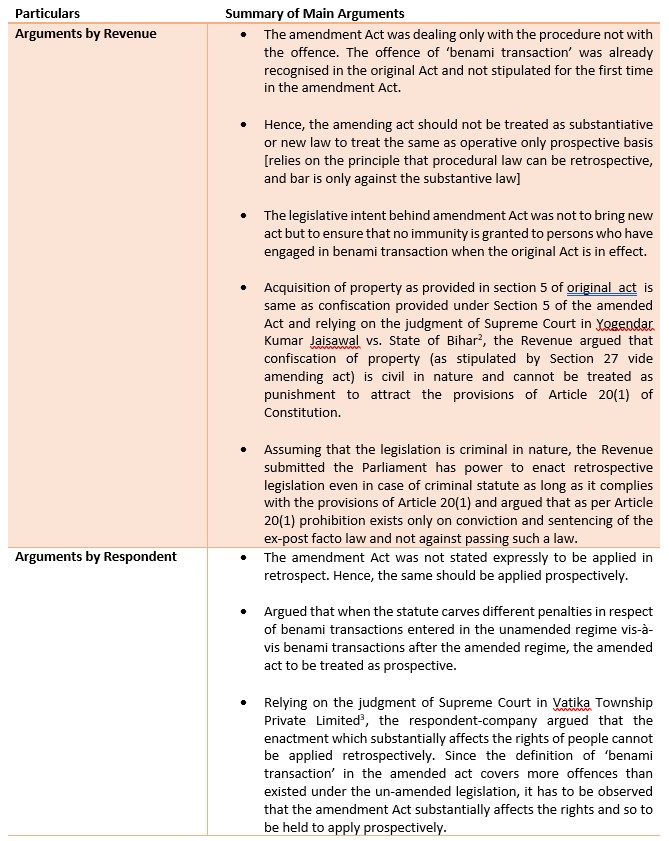

As soon as the amendment act was passed, the tax authorities have initiated the proceedings under the consolidated act (original Act + amendment Act). The said proceedings were challenged stating that the provisions of amendment Act are applicable only after the amendment Act is enacted and not for the period prior to that. Since the amendment Act was enacted only in November 2016, the tax payers/assesses contention was that the said act will apply only for transactions entered post November 2016 and transactions entered between 19.05.1988 and 01.11.2016, cannot be tried under the amended act. Further, the offence under the original Act and the amended act are different, the amended act should be treated as substantive and to be applied prospectively.

Analysis by Supreme Court:

On Types of Benami Transaction:

After tracing the history of the benami law in the country, the Supreme Court stated that there were two loose categories of transactions which were colloquially called as ‘benami’. The same were explained by way of examples:

- ‘B’ sells property to ‘A’ (real owner), but the sale deed mentions ‘C’ as the owner/benamidar (let us call this as ‘Instance – I’)

- ‘A’ sells property to ‘B’ without intending to pass the title to ‘B’ (let us call this as ‘Instance – II’)

The Court stated that Instance – I can be termed as real benami transaction and Instance – II can be called ‘loosely’ as a benami transaction [Refers to Sree Meenakshi Mills Limited[4] and Thakur Bhim Sigh[5] to arrive at the said distinction]. The Court stated that under the original Act, only the nature of transactions mentioned in Instance – I were covered and reading of the transactions mentioned in Instance – II in the definition as existed under the original Act would amount to judicial overreach, since it would be against the strict reading of criminal law.

Further, the definition of ‘benami transaction’ under the original Act is capable of covering such transactions which were held by third party in the fiduciary capacity and stated that the property holder’s lack of beneficial interest in the property which was a vital ingredient to call a transaction as benami was completely absent in the definition under original Act.

On Section 3 and section 5 of Original Act:

The Court stated that provisions of original Act completely ignore the aspect of mens rea as provisions of section 2(a) and section 3 of the original Act have been drafted as such (the concept of mens rea has been considered by the 57th law commission report but same was not integrated into the original Act).

The question now arises is, whether such a criminal provision, which the Parliament now intends to make use of, to confiscate properties after 28 years of dormancy, could have existed in the books of law?

The Court stated to answer the above, that is, whether the amendment Act is retroactive or prospective, it needs to be seen, whether the original Act was constitutionally valid? Referring to the various judgments that gave the judiciary the power to test the constitutionality of the legislations, the court stated that the provisions of Section 3 and Section 5 of original Act has to be analysed for the constitutional validity.

In the context of section 2(a) and section 3 of the original Act, the Court stated that the original Act was merely a shell, lacking the substance that a criminal legislation requires for being sustained. The Court stated that absence of mens rea in the original Act and appearance of the same in the amendment Act (vide section 53) indicates that doing away of the mens rea aspect was without any rhyme and reason and ended up creating an unusually harsh enactment.

Next, the ignorance of the vital ingredient of beneficial ownership exercised by the real owner contributes to the making the law even more stringent and disproportionate with respect to benami transactions that are in nature mentioned in Instance – I. In removing such an essential or vital ingredient, the legislature has not laid out any specific reason which makes the entire provision susceptible to arbitrariness. Further, those provisions of original Act have never been utilised as there was a significant vacuum in enabling the functioning of such provisions.

The Court stated that it is a simple requirement under Article 20(1) that a law needs to be clear and not vague, and it should not have incurable gaps which are yet to be legislated/filled in by judicial process. Accordingly, the Court held that the criminal provision under Section 3(1) of original Act has serious lacunae which could not be cured by judicial forms, even though some form of harmonious interpretation and thus fails the substantiative due process requirement of constitution.

Coming to the section 5 of the original Act, which deals with acquisition of benami property by the government, the Court further held that Section 5 is half-baked which did not provide various items and just left it to the delegated legislation, which has resulted the delegation as excessive and arbitrary and accordingly held that the Revenue stand that the amendment Act is merely procedural cannot be valid.

The Court held that the original Act is an inconclusive law, which is left the essential features to delegated legislation and hence cannot be said to be valid. The gaps left in the original Act were not merely procedural, rather the same were essential and substantiative. Accordingly, the Court concluded that Section 3 and Section 5 of original Act were unconstitutional from the inception. However, by adopting the concept of ‘prospective overruling’, the Court stated that the above discussion does not affect the civil consequences contemplated under Section 4 of original Act or any other provisions.

The Court stated that since the Section 3 and Section 5 of original Act were held to be unconstitutional, the changes brought by amendment Act must be understood as new provisions and new offense and thus cannot be called as retroactive. Finally, coming to the argument of Revenue that acquisition of property and confiscation are same in nature and such confiscation is civil in nature, the Court held that the attachment arising in the case of benami transaction is punitive in nature and cannot be said to be civil. Accordingly held that the same cannot be applied retroactively.

On Section 3 of Amended Act:

Further, the amended act provides separate punishments/consequences for those transactions which are entered between an enactment of original Act and amended Act, and for those transactions which are entered transactions after the amendment Act. In respect of these, provisions, the Court went on to state that concerned authorities cannot continue proceedings in relations to transactions prior to amendment even though the amended Act.

Concluding Remarks:

Rajasthan High Court in the case of Niharika Jain[6] has held that provisions of amendment Act cannot be applicable retrospectively owing to substantial changes in the Act and introduction of additional penal provisions into the Act. However, Chhattisgarh High Court in the case of Tulsiram and Manki Bai[7] has held that amendment Act has not repealed or superseded the original Act in any manner. Further, section 3(2) specifically provides for transactions entered before the enacting the amendment Act and the intention of the parliament is to cure loopholes in original Act and not to repeal the original Act.

However, the Supreme Court has struck down such section 3(2) of the Amendment Act stating the transactions entered before the enactment of amendment Act cannot be persecuted or penalised.

As far as the amendments are concerned, original Act does not have full mechanism to enforce such law against benami transactions. As stated earlier, to remove such anomalies, Government has decided to make substantial changes to Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988. Such an objective can be achieved by the Government by enacting a separate new bill instead of making amendments to original Act. But Government acting on the advisory of Ministry of Law (as discussed in the introduction of the article), has decided to make amendments to original act and there is a sound and logical reason in bringing amendment act, even though there are just 9 sections in the original Act, instead of new separate Act. Bringing a new law may provide immunity to past transactions hence, Government has decided to make amendments to existing law by way of passing amended bill.

The then Hon’ble Finance Minister, in respect of question asked by the member of Parliament why Government is introducing an amendment bill instead of new bill, has stated that ‘Anybody will know that a law can be made retrospective, but under Article 20 of the Constitution of India, penal laws cannot be made retrospective. The simple answer to the question why we did not bring a new law is that a new law would have meant giving immunity to everybody from the penal provisions during the period 1988 to 2016 and giving a 28-year immunity would not have been in larger public interest, particularly if large amounts of unaccounted and black money have been used to transact those transactions. That was the principal object. Therefore, prima facie the argument looks attractive that ‘there is a 9-section law and you are inserting 71 sections into it. So, you bring a new law.’, but a new law would have had consequences which would have been detrimental to public interest.’

In other words, the Government has fair idea of the consequence/outcome if new enactment is made, as such new act would be effective prospectively and cannot be applied retrospectively owing to challenge from Article 20 of the Constitution. However, the above objective was not considered by the Supreme Court. Accordingly, the Government, even after bringing amendment Act, has not achieved the intended objective. Therefore, all the transactions entered between the said dates have been granted immunity and all proceedings initiated would be required to be dropped. The proceedings for subject matter of property which was acquired after the amendment act was made effective can only be pursued by the tax authorities. It is highly likely a review petition would be filed by Revenue before the Supreme Court asking to consider the intention and objective behind passing the amendment act instead of getting a new act.

[1] AIR 1918 PC 140

[2] [2016] 3 SCC 183

[3] [2015] 1 SCC 001

[4] AIR 1957 SC 49

[5] AIR 1980 SC 727

[6] CW-2915/2019

[7] Writ Petition (C) No. 3819 of 2019